The trial has opened in the Netherlands of three Russians and a Ukrainian – still at large – for the murder of 298 people aboard Malaysia Airlines flight MH17, shot down over Ukraine in 2014.

The Boeing 777 went down amid a conflict in eastern Ukraine, after Russian-backed rebels seized the area.

Investigators say they have proof the Buk missile system that shot it down came from a military base in Russia.

A judge called it an “atrocious disaster”, as proceedings began.

The trial is in a court near Amsterdam’s Schiphol airport, the departure point for the Kuala Lumpur-bound flight.

Head judge Hendrik Steenhuis said there had been a “tragic loss of human lives from all around the world”.

Russia has repeatedly denied involvement in the deadly attack on 17 July 2014. Citizens of 10 different countries died on the airliner.

The three Russian men and one Ukrainian man from eastern Ukraine are all linked to the heavily armed pro-Moscow separatists.

Neither country extradites its citizens but one of the Russians will have a defence team in the courtroom, and the court says it is also prepared to accept testimony from them by video link.

The roar of planes is audible. Schiphol’s high-security justice complex is right next door to the runway where flight MH17 took off. But no-one is expecting any of the four suspects to fly in to face justice.

This trial is the culmination of the most complex criminal investigation in Dutch history.

Two thirds of the victims were Dutch; the Netherlands took the lead in the investigation and the trial will be held within the Dutch legal system.

Two weeks have been allocated for the start, which will cover mostly procedural aspects and establish whether indeed the trial will be conducted in absentia, without the accused.

Victims’ relatives will have a chance to tell the court how their lives have been affected and what they see as the most appropriate punishment.

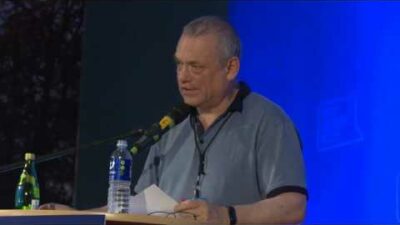

Piet Ploeg’s nephew came back in 80 pieces and Mr Ploeg keeps the list of body-parts in his safe. His brother Alex’s remains have never been found.

Piet Ploeg has no expectation the accused will appear even via video link, or that they’ll serve time if convicted of mass murder.

But the trial matters for him and so many other relatives, because for them it’s the only key to unlocking “the truth”.

“We want the world to know what really happened”, he told me, “and to know who did it.”

On Sunday, relatives of MH17 victims lined up 298 empty seats outside the Russian embassy in The Hague to commemorate their loved ones and protest over Russia’s stance.

Image copyrightEPA

Image copyrightEPAWho will give evidence?

Little is known about who will testify before the court’s three judges.

Unconfirmed Dutch reports say there are 13 witnesses whose identities will remain secret, but the judges may decide that anyone who has already given evidence to prosecutors may not need to appear in person.

Image copyrightREUTERS

Image copyrightREUTERSThe court will be able to hear anonymous testimony if necessary, in a trial that could take more than three years.

Who are the suspects?

Two of them allegedly have ties to Russia’s GRU military intelligence agency, which has been linked to cyber-plots as well as the deadly nerve agent attack on Salisbury in England.

The four men are:

- Igor Girkin, also known as Strelkov. He is a former colonel in Russia’s FSB intelligence service, given the title of minister of defence in the rebel-held eastern Ukrainian city of Donetsk, prosecutors say

- Sergei Dubinsky, known as Khmury. He was employed by Russia’s GRU military intelligence agency, according to investigators. They say he was a deputy of Mr Girkin and in regular contact with Russia

- Oleg Pulatov, known as Giurza. He is allegedly a former soldier with GRU special forces who became deputy head of the intelligence service in Donetsk

- Leonid Kharchenko, known as Krot. He is a Ukrainian national with no military background who led a combat unit as a commander in Eastern Ukraine, say prosecutors.

The four are accused of murdering 298 people and causing the MH17 crash. Prosecutors say the men are jointly accountable for the attack because they “co-operated to obtain and deploy” the Buk missile launcher in order to shoot down an aircraft.

Court summonses were sent to all four although it is not certain that the men received them, so one early task for the court will be to decide whether sufficient effort was made to reach them.

Significantly, one of the suspects, Oleg Pulatov, will be represented by a defence team, so the court may decide he is not considered in absentia. Igor Girkin has told the BBC he does not recognise the court’s authority.

In recent years, Russia’s usual reaction to being accused of anything has been denial.

MH17 is no exception.

Moscow insists it had nothing to do with the shooting down of the Boeing. And ahead of the trial in the Netherlands, Russian officials have been trying to discredit the proceedings.

Foreign ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova told me she was “100% certain that politics is dominating” in the court case. She said that Moscow had provided Dutch investigators with “tons of materials on this case which were disregarded”.

When I asked Russian state TV talk show host Vladimir Solovyov about the trial, his reaction was: “We don’t care. We want to get the truth, but how can we when the whole investigation was far from truthful?”

As for the suspects, three of whom are Russian citizens, they had little to fear from the international arrest warrants issued last year. Russia’s constitution does not permit the extradition of its own nationals.

Did Russia impede the investigation?

Although Russia argues it has long offered to co-operate with the inquiry, it has also presented several versions of what brought down MH17.

Dutch officials asked Russia to submit any information they had, but said at one point that the information it had provided was “factually inaccurate on several points”.

Late last year, Russia was asked by Dutch prosecutors to arrest a Ukrainian suspect alleged to have run rebel air defences close to the missile firing site. Instead, according to prosecutors, Russia deliberately allowed him to travel to eastern Ukraine.

The Dutch and Australian governments made clear in 2018 they held Russia responsible for the deployment of the Buk missile launcher that brought down the plane.

Audio transcripts disclosed by the investigation team last year suggested rebels in eastern Ukraine had close contact with Russia at the time. The head of the self-styled Donetsk People’s Republic was recorded a fortnight before the disaster saying he was “carrying out orders and protecting the interests of one and only one state, the Russian Federation”.

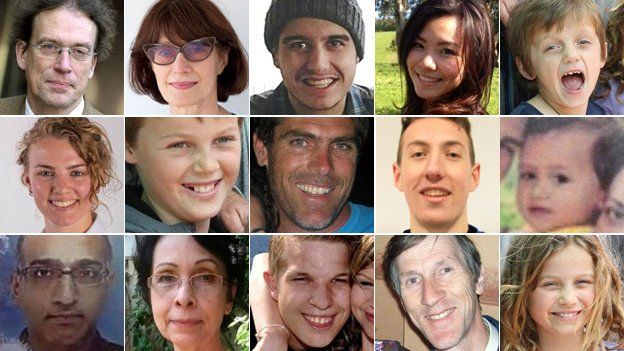

Who died on MH17?

Image copyrightVARIOUS

Image copyrightVARIOUS- 193 Dutch

- 43 Malaysians (including 15 crew)

- 27 Australians

- 12 Indonesians

- 10 Britons

- 4 German nationals, 4 Belgians

- 3 Filipinos, 1 Canadian and 1 New Zealander